On November 19, 1863, four months after the Battle of Gettysburg, a ceremony was held at the site in Pennsylvania to dedicate a cemetery for the Union dead. The battle had been a Union victory, but at great cost—about 23,000 Union casualties and 23,000 Confederate (a total of nearly 8,000 killed, 27,000 wounded, and 11,000 missing). At the cemetery dedication in November 1863, the day’s speakers found themselves tasked with finding the right words to commemorate those who had perished in the bloodiest battle of the Civil War.

The main speaker was Edward Everett, a former US senator, governor of Massachusetts, and president of Harvard. President Lincoln had been invited to make a "few appropriate remarks" at the cemetery’s consecration. Some 15,000 people heard his speech.

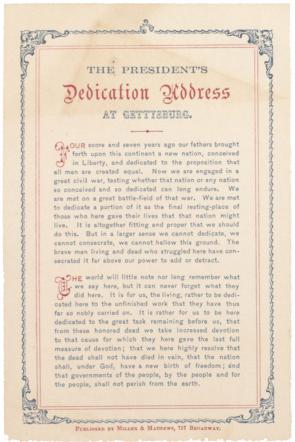

Less than 275 words in length, Lincoln’s three-minute-long Gettysburg Address defined the meaning of the Civil War. Drawing upon the biblical concepts of suffering, consecration, and resurrection, he described the war as a momentous chapter in the global struggle for self-government, liberty, and equality. Lincoln told the crowd that the nation would "have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth." He stated that the Union had to remain dedicated to "to the great task remaining before us" with "increased devotion to that cause for which" the dead had given "the last full measure of devotion."

In his short address, Lincoln honored the fallen dead and framed those soldiers’ sacrifices and the war itself as necessary to the survival of the nation. The copy of the address printed here has textual errors that indicate it is a very early printing.

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

Read the document introduction and transcript and apply your knowledge of American history as well as evidence from the document in order to answer these questions.